Sweeping worms

How a single moving filament gathers particles without grabbing

Imagine dropping one aquatic worm into a dish sprinkled with sand grains. The sand doesn’t stick. The grains don’t drift on their own. And yet, over time, the worm “cleans up” its surroundings, sweeping scattered grains into compact piles.

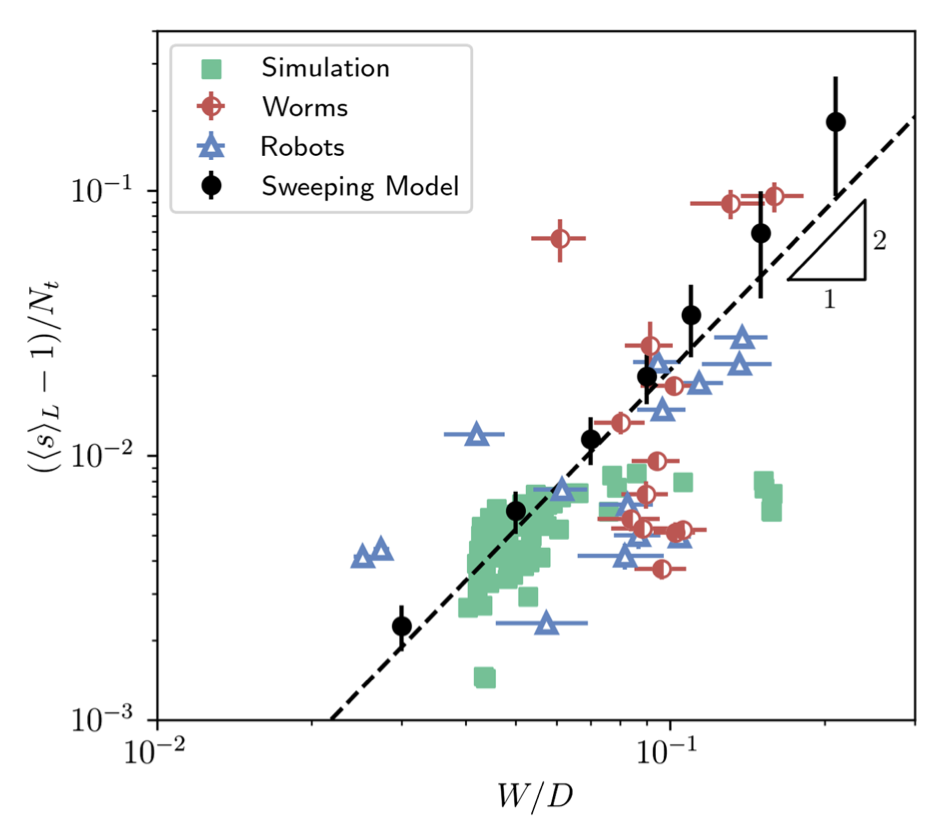

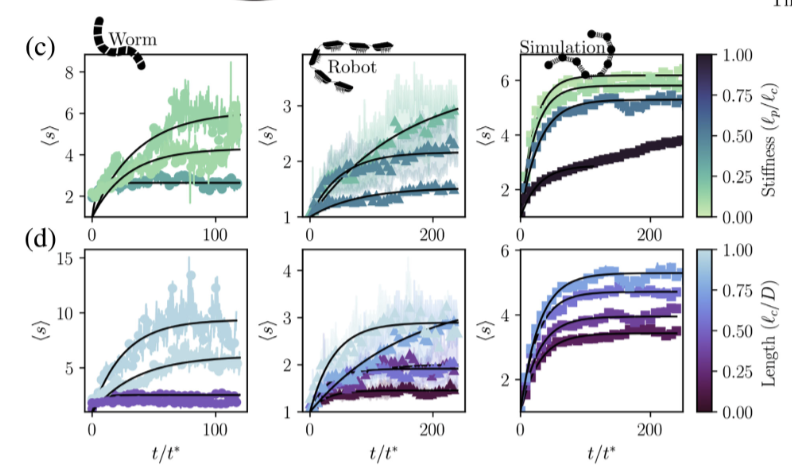

In this work, we show that this is not a special worm trick. It’s a physical mechanism that appears across living worms, a meter-scale robot chain, and active-polymer simulations: a moving flexible filament repeatedly clears a path and nudges particles into clusters. The key control knob is geometry. The wider the filament’s swept “footprint” W, the larger the clusters it builds at steady state (roughly scaling like W²).

Across all systems, how much material is gathered is controlled by how widely the filament sweeps, linking geometry, flexibility, and motion to particle collection in a single, unified framework.

Our robot sweeps and gathers particles just like a living worm.

Major questions

Can a single moving body organize particles by contact alone?

What sets how much gets collected: speed, flexibility, length, or something simpler?

Can we build a robot that “cleans” without grippers, suction, sensing, or centralized control?

What we’ve discovered

A single filament can do the work of many “active particles”

Most particle-collection strategies in active matter rely on swarms of active units. Here, one extended, self-propelled filament is enough to generate clustering through repeated contact and body deformation.

The design rule is the sweep width

Across worms, robots, and simulations, cluster size is controlled by the width of the cleared path, W, the filament’s effective footprint. When W is larger, the filament corrals particles into larger clusters. At steady state, the average cluster size grows approximately like W² (relative to arena size).

Collection saturates because the filament also breaks clusters

The filament is both a builder and a breaker: it pushes particles together, but it also fragments clusters when it plows through them. These competing processes balance, leading to a natural steady state rather than runaway growth.

Collection converges in a fixed number of “sweeps,” not a fixed number of minutes

If you measure time in units of how long the filament takes to traverse the arena, worms, robots, and simulations reach steady behavior after on the order of a few dozen sweeps.

Robot geometry is a control knob for collection

By changing filament geometry (flexibility, branching, built-in curvature, or speed asymmetry along the chain), we tune the footprint width W and therefore tune how much gets collected, without adding sensing or centralized control.

Where the piles end up depends on length and exploration pattern

Long filaments tend to concentrate clusters toward the arena center, while short ones leave particles more peripheral. Centralization also depends on how the filament explores the arena (very flexible trajectories can sometimes push clusters outward).

What others are saying

“The framework presented in this work could lead to the development of simpler robotic materials capable of performing tasks without the need for external control or feedback.”

- Emanuele Locatelli, APS Physics Viewpoint, University of Padua

Watch the videos to learn more!

Read the paper

Particle Sweeping and Collection by Active and Living Filaments. Physical Review X (2026)

Worm-Inspired Active Filaments Sweep Disorder into Order. Physics Viewpoint (2026)