Hopping Mudskippers

The secret to mudskipper hopping: How fish learned to skip on water

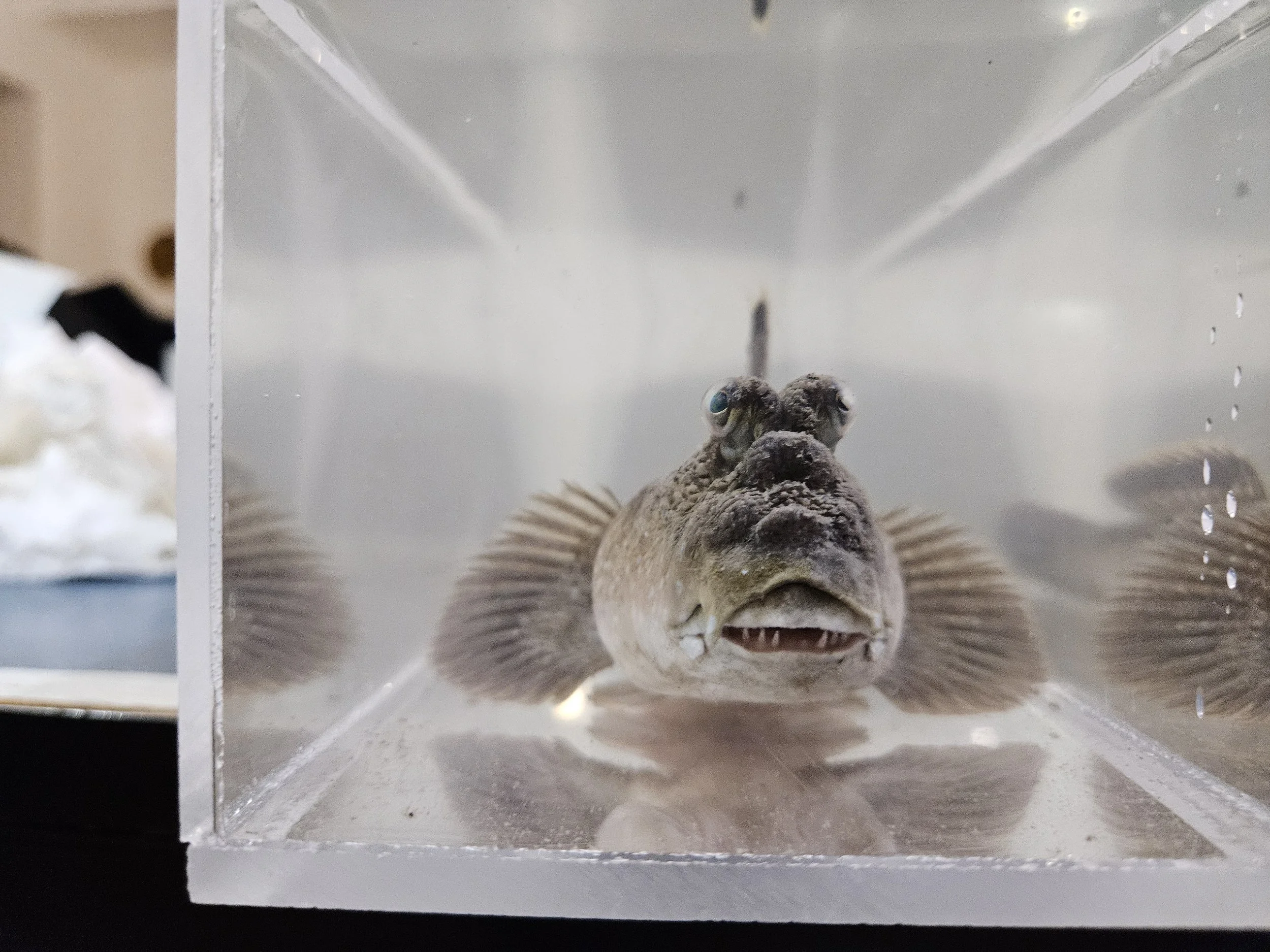

If you’ve ever wandered a tidal flat at low tide, you might catch sight of a small fish that seems to defy biology’s categories: part swimmer, part climber, part acrobat. Meet the mudskipper, an amphibious fish that can breathe through its skin, perch on mangrove roots, and, as we demonstrate, hop across the surface of water like a skipping stone comeing to life.

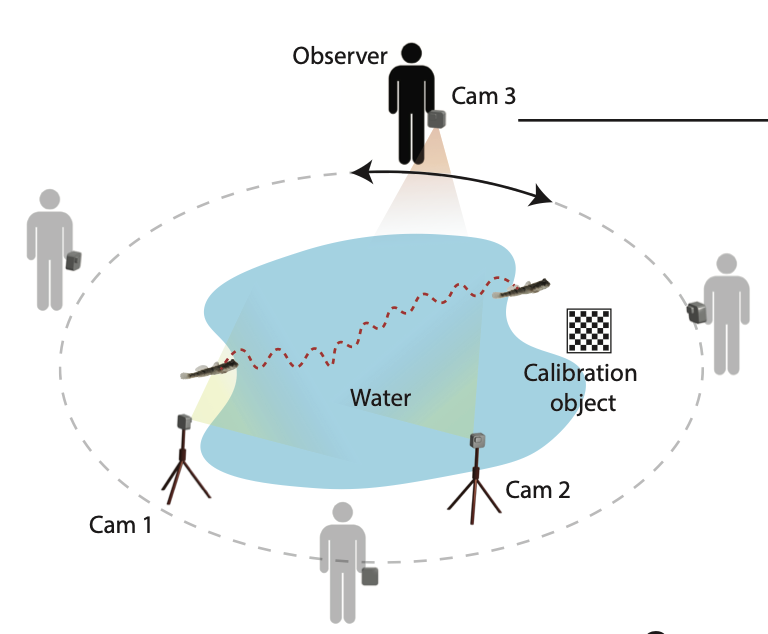

Capturing motion on the mudflat

We set out to capture this elusive motion not in the lab, but in the field. Using a pair of portable cameras, a 3D reconstruction algorithm, and a lot of patience, we developed a low-cost, field-deployable system to track mudskippers as they dart and leap across the shimmering boundary between sea and sky. We found that these fish hop-and-glide, with each hop powered by a rapid flick of the tail and guided by subtle fin movements. Their trajectories aren’t random; they reflect the fish’s size, terrain, and escape strategy when startled by predators. From the muddy shores of South Korea to the mangrove islands of Brunei, our cameras captured a fascinating ballet of physics and biomechanics, revealing how these small creatures navigate complex, shifting environments with seeming grace and agility.

Major questions

How can we capture hopping behavior of mudskippers in their natural tidal-flat habitats?

What kinematic patterns define water-hopping in mudskippers?

Do mudskippers exhibit distinct modes of hopping?

How can we develop a portable, noninvasive 3D tracking method to study mudskippers in their natural habitats?

What we’ve discovered

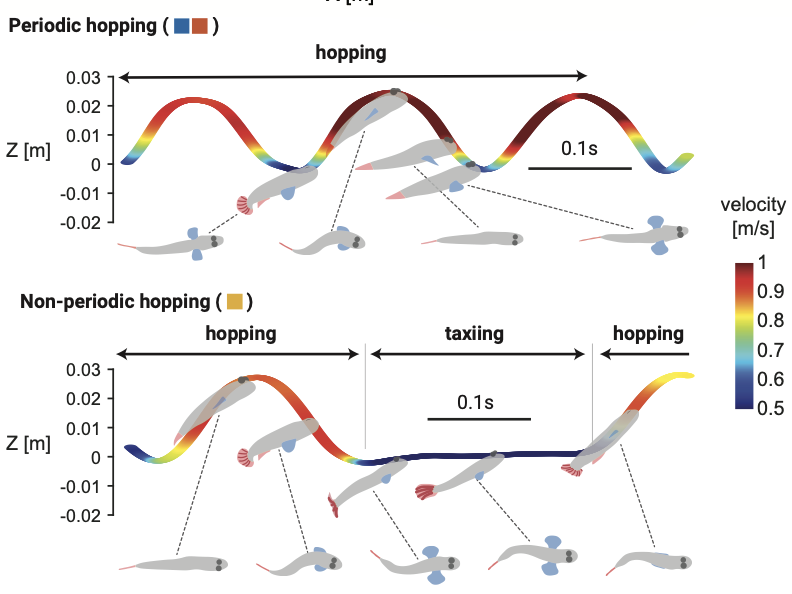

Two Ways to Hop

Mudskippers use two distinct movement styles: rhythmic periodic hopping across the surface, and nonperiodic hopping that mixes short glides or “taxiing” between leaps. Most of the time, they stick to the steady, repeated hops, likely their most efficient escape strategy.

Every Hop Follows a Pattern

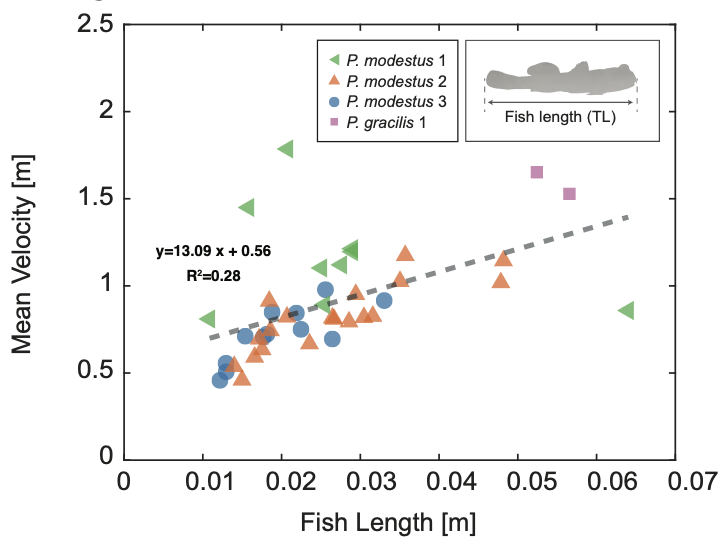

Each hop follows a predictable parabolic path, similar to the ballistic motion seen in frogs or flying fish. Using our 3D tracking, we measured velocity peaks with each takeoff and found that both hop height and stride length scale with body size up to a critical threshold (~4 cm in body length). Beyond that, performance plateaus, likely due to the balance between muscle strength and body weight

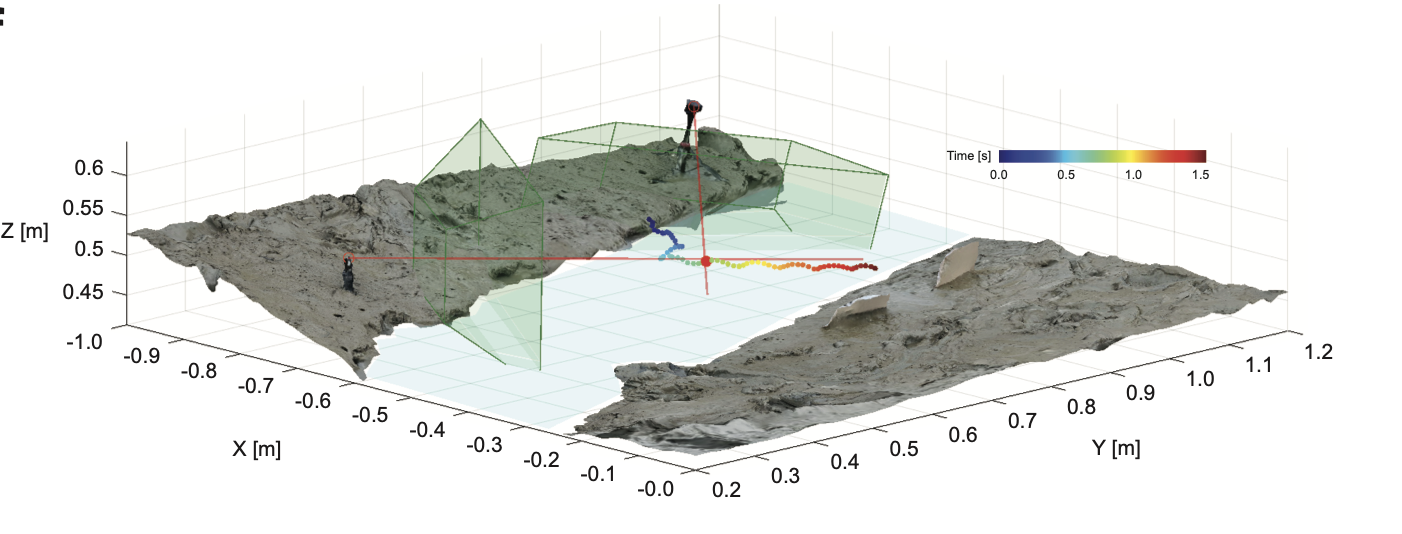

Tracking Every Millimeter

Our 3D tracking system captured each hop with millimeter-scale precision, even in muddy, unpredictable field conditions. This portable setup revealed the full motion of fins, bodies, and trajectories that were invisible in single-camera studies.

Terrain Shapes Motion

The reconstructed 3D environment revealed that local topography and water depth strongly influence hopping behavior. Mudskippers adjusted their path curvature and turning angles to avoid obstacles and respond to predator cues. By mapping terrain and trajectory together, we could visualize how these fish navigate the ever-changing boundaries between land and water.

Speed Grows with Size

We found that mean hop velocity increases with body length. However, beyond a certain size, speed gains begin to level off, indicating biomechanical limits in how thrust scales with mass

From Biology to Bio-Inspired Design

Understanding how mudskippers hop efficiently on water reveals engineering principles that can inform amphibious robot design. Their balance between thrust, lift, and surface tension demonstrates how nature achieves stability and propulsion on deformable boundaries, insights that we are currently translating into mudskipper-inspired hopping robots.

Read the paper

Three-dimensional Tracking Method for Water-Hopping Mudskippers in Natural Habitats. Integrative & Comparative Biology. 2025.